I gave a talk to open the 2025 Arrow Summit in Paris, looking back at the history of the Apache Arrow project, some factors that have contributed to its success, and what the past can tell us about how to ensure a bright future. The talk wasn’t recorded, and while I’ve published the slides, they don’t alone capture what the talk was like, so I thought I would publish a version of it in blog form here.

Arrow was established as a top-level Apache Software Foundation (ASF) project in January 2016.

The first commit in the apache/arrow repository was in February 2016.

That means it is approaching its 10th birthday.

This year, I’ve been reflective about this milestone, and what it means for the project and the community, for two reasons.

The first is that I see lots of new projects and startups in the data space, and when they talk about their tech stack or show architecture diagrams, Arrow is everywhere. It’s not just everywhere, it’s taken for granted that if you’re building a data system, you’re using Arrow.

For example, I was at the Data Council conference in Oakland back in the spring, and I kept seeing slides that just had Arrow everywhere. In Julien Le Dem’s talk about the new data stack, the “Deconstructed Database” and the “Open Data Lake”, Arrow is what connects everything. And then Ciro Greco from Bauplan showed their architectural diagram with lots of Arrows.

And it struck me how different of a world this is from when Arrow started, or even when I got involved in the project back in 2019. It was definitely the aspiration to have Arrow connecting everything, but it was not a guarantee. Seeing all of these presentations talking about Arrow as if it is part of the air we breathe, taking it for granted, I found it overwhelming–in a good way.

The second reason I’ve been reflecting on this is more personal: my son, James, turned 10 this year. That also got me reflecting on the passage of time, and what it means to support and nurture something over a long period of time, watching it grow and change, and really develop its own identity and trajectory.

Arrow is different from most open source projects, in scope and in ambition. Trying to create a ubiquitous standard is not something most projects aspire to. There’s a different time scale, a different level of patience and persistence required, than building a tool to solve a specific problem.

And as I was reflecting on that, I realized that there are parallels with raising a child—also a long-term investment, with a lot of uncertainty about what the future will look like, and what they will become. Ultimately, you’re trying to nurture something that will become self-sustaining, and go beyond the limits of my imagination for them.

I’ve been fortunate to be a part of Arrow’s journey for the majority of its life. So today I want to share some thoughts about the project and the community, and in particular some of the non-technical factors that have contributed to its success. Understanding how Arrow got to where it is today can help us understand how to ensure its future.

Before we get any further, I should introduce myself. I first got involved with Arrow in 2019, when I joined Ursa Labs to help coordinate and fund development of Arrow and related projects. Arrow sounded like a good idea, and I wanted to help make it happen. I’ve been a member of Arrow’s Project Management Committee (PMC) since 2020, and am currently serving as its chair. Before I got into software, I was a political scientist. Usually, that’s not relevant. But today, some of that may come through in this talk.

It should be clear that the views and perspective I’ll be sharing today are colored by my own experiences. One of the things I love about the Arrow project is that is so expansive, and there are subprojects that I haven’t been involved in much. I want to try to draw some general lessons from my experience, and I hope that others see themselves in them, but if I fail to mention your part of the story, please forgive me, I’m not trying to suggest that only the parts I’ve been involved in matter.

Non-technical factors

I say “non-technical” for a couple of reasons. First, I don’t need to tell you how Arrow speeds up data workflows and improves interoperability. You’re going to hear some great talks today that will cover that, and chances are that if you’re here, you already have a sense of the technical merits of Arrow.

Second, because I think that the technical aspects are necessary but not sufficient for a project like Arrow to succeed in becoming ubiquitous. The fundamental challenge for a project like Arrow is to get other developers to choose to be a part of the ecosystem, to build on it, rather than going their own way. Yes, the tech matters, but this is a social challenge. We were trying to change behavior, trying to change people’s expectations.

As I was preparing this talk, I saw this post from JD Long that was if he was reading my mind. He was talking about the adoption of MCP as a standard, but the same thing holds. All software on some level is a social experiment, an attempt to change your behavior—to get you to use my library, buy my product, and so on. But for Arrow, the social challenge is front and center. It’s core to the vision. If you don’t get people to build on it, then it won’t become a standard, and then it won’t be useful. You have to change behavior.

The one-line summary of Arrow currently on the website says that Arrow is “the universal columnar format and multi-language toolbox for fast data interchange and in-memory analytics.” Arrow is about interoperability, and that means that you really get the most value out of it when everything is built with it.

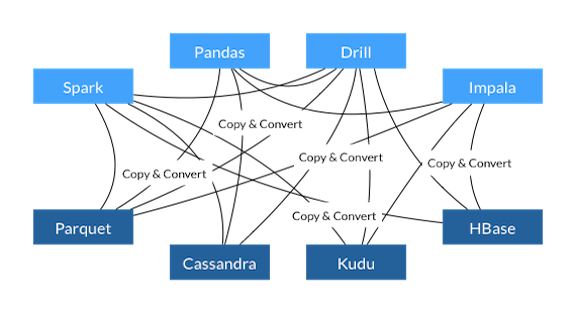

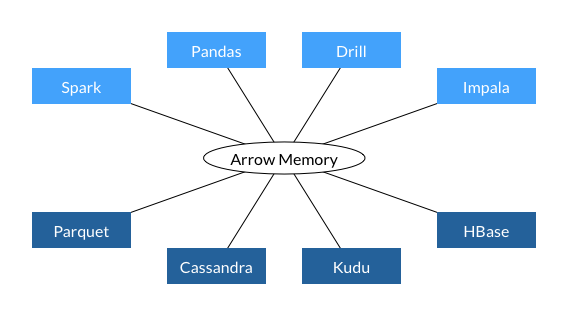

This was the point from the beginning. There’s this pair of graphics that’s been on the website for as long as I can remember:

The idea is that all of these projects would only need to implement one export and import format, not N different ones, in order to integrate with each other. Sounds great! But that means, from the Arrow perspective, that you still have N projects you need to get to adopt your one true format. And the value of that format increases with the number of projects that adopt it—but it’s zero value for the first project to implement it. So you have a chicken-and-egg problem, and you need to convince people to change their behavior.

But the ambition of Arrow is actually bigger than just writing adapters. In fact, I content that Arrow is actually a radical social project.

There is something more revolutionary in the vision there about decoupling everything. If data storage and compute are unbundled, you can mix and match the best components for your use case. You can choose the best compute engine for your needs, potentially multiple engines for each special application, and have these different layers work together seamlessly.

So it’s not just: use my library because it’s faster. Or even: adopt this standard because it’s more efficient. It’s: rethink how you build data systems.

That was an ambitious vision: a technical one, yes, but also a social one. Getting people to buy into that vision, and to build on it, is a challenge, just as much as it is to design the right specification and implement it in fast libraries across multiple languages.

Maybe you haven’t thought of yourself as being part of a radical agenda (maybe you do!), but in my estimation, that’s what you have been doing.

But in order for the revolution to succeed, we had to overcome some forces that worked against us, that created incentives for developers not to join us. In the beginning, Arrow faced a collective action problem, to borrow a concept from economics and political science. Everyone would benefit if we all used the same memory format. But building it is expensive, and it’s not worth it to any individual developer or project to take on making it happen. This is the free-rider problem. Of course, if everyone free rides, no one does the work, and we don’t have a standard.

Another way of thinking of it is as a coordination problem. How do you get enough of the developers working on these various data projects, as well as their corporate overlords, to invest in the common good? How do you make it safe, and even rational, for them to cooperate and fund the work, rather than completely free ride.

There were several forward-looking, strategic actions that some of the initial Arrow developers took to address this.

Governance

The first is governance. Arrow is part of the ASF, which provides an aegis for individuals to come together and work on software in a vendor-neutral, self-governed space. In an ASF project, everyone contributes as individuals, not as representatives of their companies, and being employed by some big company doesn’t give you any special privileges. All authority in the project is earned: the project is self-governed by the PMC, which is responsible for maintaining the integrity of the project, including offering commit privileges to new contributors and even inviting new members to the PMC. Those decisions are based on an individual’s sustained pattern of engagement with the project. These values are capped off by the foundation’s mantra, “community over code,” which means that focusing on how people work together is more important than technical purity. A healthy community can fix technical problems, but perfect code can’t fix a broken community.

Open governance doesn’t solve the coordination problem by itself, but it is a form of commitment device that removes some of the risk of cooperating with others. It makes it safe for companies that are otherwise competitors to collaborate on the project. And in practice, we’ve seen that happen.

All ASF projects also use the Apache 2.0 license, a “free-as-in-freedom” license, which also is important for others to freely adopt the software without meaningful restrictions. Taken together, these all signal that Arrow is safe to depend on, safe to build into your projects.

Contrast this with a scenario where Arrow was something being developed by one big company or vendor. If the technology were good, you might still build on it, but you would know that you are carrying a risk, a risk that the company that owns it could decide to make choices that would benefit their products and squeeze yours. To hedge, you might not rely solely on Arrow, so that you could make sure your product (and potentially your whole business) could survive that loss. That would be pressure against the goal of establishing a ubiquitous standard.

Fundraising for fundamentals

The second early step towards making Arrow happen was fundraising, so that people could be paid to build out the technical foundations for Arrow.

Volunteer work is great and is essential for open source and Arrow in particular. But volunteer work tends to underfund foundational maintenance work, because it’s not as exciting as building a new feature or a new tool. Most people don’t choose to spend their free time fixing build systems, or reviewing pull requests from other people (who got to do the fun stuff!).

Dremio, with Jacques Nadeau and others, made a big bet on Arrow early, and hired several people to work on it full time, particularly in Java. Most companies did not jump on board so much.

Wes McKinney was intially supported by Two Sigma, but he wanted to go bigger, so he partnered with RStudio (now Posit) to establish Ursa Labs in 2018 to help coordinate and fund development of Arrow and related projects. That’s where I joined in 2019, and we worked to source contributions from a number of companies to fund development, and hired a team of engineers to work on Arrow full time.

Of course, we weren’t alone in contributing to Arrow, but at the time a high volume of contributions came from this team, in particular in these foundational areas, and we also made a point of investing heavily in code review and other maintainer activities to enable those who maybe didn’t have the ability to dedicate as much time to Arrow to be able to contribute effectively.

I viewed the work we did at Ursa Labs as about trying to solve the collective action problem, by providing a way for companies to pool their resources to fund development of Arrow.

Among the initiatives we supported were around build systems and packaging, including on a range of esoteric platforms. This also required continuous integration everywhere, and there was a very clever system of launching jobs on basically every CI platform at the time that gave free credits for open source projects. There are currently around 300 different jobs that get run, some on every commit, some nightly or on demand.

Another big push was with integration testing, so that we could validate that the various independent implementations of the Arrow specification, in different languages, were fully compliant with each other and with the spec. Filling out this integration test matrix allowed us the confidence to declare the 1.0 release of Arrow in 2020.

All of this work was (and still is) deeply technical, of course! But at least for the work I was involved in, there were always two goals in mind. the immediate technical goal, of course, but also keeping in mind the social aspect, changing behavior, of getting people to believe that it was safe and wise to build on Arrow, that we said this was going to be the standard, and we were grinding in order to make that a reality. It is unglamorous work, but it was essential to establishing the trust that the libraries are safe, complete, and reliable to build on.

The 1.0 release was an important milestone, but ultimately not a technical one; the difference between the contents 0.15 and 1.0 libraries was not as significant as the signal of “1.0”. The format had de facto been stable for many releases prior. However, while many projects had started adopting Arrow prior to 1.0, many more were waiting for 1.0 as a signal that Arrow was stable.

Early proof points

The other thing that the project developers did in the early days was establish some demonstrations of the potential of Arrow. To become a standard, you need wide adoption. That means there need to be compelling reasons to use it, not just the removal of reasons not to use it.

The feather library, released in 2016, implemented a simple subset of Arrow in R and Python, and showed both that a well-designed columnar format could yield performance gains over alternatives like CSVs, and that by having a language-independent format, you could get great interoperability between Python and R. Saying this now, it seems obvious that you could interoperate with data frames across those languages, but it was just not feasible to do ten years ago.

Another demonstration of the potential was in the pyspark integration, which delivered orders of magnitude speedups between Apache Spark and Python. Historically, using pyspark instead of the Scala libraries for working with Spark entailed a sigificant performance penalty, and Arrow helped close the gap and make Python a much more useful language for working with Spark. For Arrow, this use case was interesting because it leveraged distinct implementations of the Arrow format, Java and C++. It showed the value of having a standard that was not tied to any single language’s implementation details.

Then, there were a series of “draw the rest of the owl” kinds of projects. Like, if Arrow is so fast reading from Spark, why not make the whole thing out of Arrow? With DataFusion in 2018, Andy Grove wanted to show that you could use Rust for data science and computing, so he built on the Rust implementation of Arrow, and eventually donated the project to Arrow (it later spun back out as its own ASF project). Similarly, Acero, the C++ execution engine (2021), sought to be a reference implementation of a fully Arrow-native query engine.

These were all great technical achievements on their own, but they had the dual purpose of demonstrating the radical vision of an Arrow-native world.

Great, so at this point a few years in, we’ve demonstrated the potential of Arrow, and we’ve been grinding to build out the foundational libraries and infrastructure to make it possible for people to build on Arrow. We’ve removed a lot of the risk of building on it, by having a solid governance structure, and by building out the technical foundations and getting to a 1.0 release.

And because it’s liberally licensed, you’re not locked in. If you find issues with the libraries, or have a use case that you want to see supported in it, you can fork it and do your own thing if you need to. That’s good, right?

Unfortunately, for a project like Arrow, forking is harmful for our goals. The core value of Arrow is that it is a standard. If everyone forks it and makes their own “Arrow-ish” flavor, then you don’t have a standard anymore. So you don’t get the seamless interoperability, and your “deconstructed database” accumulates a bunch of friction.

So we as Arrow maintainers have to work harder to encourage developers to contribute to the core Arrow libraries, and engage with the community about the format. Because it is possible to fork, we have to work extra hard—we have to earn it.

Governance is not enough

ASF governance—everything in public, self-governing, etc.—sets us up to be able to draw people in. But it’s not sufficient. Having a governance model based on “earned authority,” and that “doers decide,” is great, but who is able to “do”? Saying we value “community over code” is great, but who feels welcome to be a part of the community?

Because we as maintainers of Arrow need to draw everyone into the standard, we need to work hard to encourage new contributors, and to make it easy for them to contribute. We want to keep them from feeling like they only way they can make progress is to fork Arrow and fragment the ecosystem.

This means many things, including building relationships with other projects and communities. But it also means just being welcoming everywhere and actively encouraging new contributors. I remember many times receiving a bug report or enhancement request, and if it were small enough, giving the reporter a pointer as to what the fix might look like and ask if they would be interested in submitting a pull request to do it. Sometimes they would say no—but sometimes they would say yes!

When issues like these would get reported, I could have just made the fix myself and it would have been faster. However, though the technical end result would be the same, the social end result would be very different. By inviting the reporter contribute, we could have the bug fix and someone new who feels like they had a hand in making this project. Maybe that would make the more likely to use our tools. Maybe if they had a positive experience engaging with us once, they would come back and do it again. you never know whether that person might end up as a core maintainer one day.

Alenka Frim, at her great PyData keynote on Tuesday, touched on these and other things that Arrow maintainers do to try to make it less scary to start contributing, from adding “good first issue” and other labels on issues in GitHub to just being responsive and eager to help on pull requests. She also was one of the authors of the New Contributor Guide on the Arrow documentation site, which is fantastic. Have a look at it: not only is it extensive, even including some language-specific tutorials, but the overal tone and structure is just right. Independent of the specific content of the pages, it sends a clear signal to the reader: you’re welcome here, we’re glad you’re interested in joining us, and we’re here to support you.

All of this effort to be open and welcoming to new contributors is something I’m very proud of supporting in my time working on Arrow. Every current member of the PMC at some point had a first commit, a first interaction with the project, and it must have been positive enough for them to keep coming back. Every first time issue reporter and contributor is a potential future PMC member, given enough time and support to become a part of the community.

So I think it is a combination of these factors–yes, technical excellence, but these non-technical factors as well–that have helped Arrow get to where it is today. Other open source projects may not need to work as hard to be open and inclusive in order to achieve their goals. But for Arrow and its radical agenda, these extra layers are needed to maintain the center of gravity, to keep pulling projects in.

I think it is safe to say that the original collective action problem has been solved. Based on what I see, Arrow has reached a critical mass, and because of the network effects, it is now the default choice for new data systems. It’s worth it for new projects to build on Arrow because so many other projects are already doing so, no need to solve a coordination problem to get them there.

“New projects” is an important phrase here. This gets to the revolutionary vision of Arrow, and of changing the behavior of developers who are building new systems, to build them along these decoupled lines, with Arrow as the common foundation.

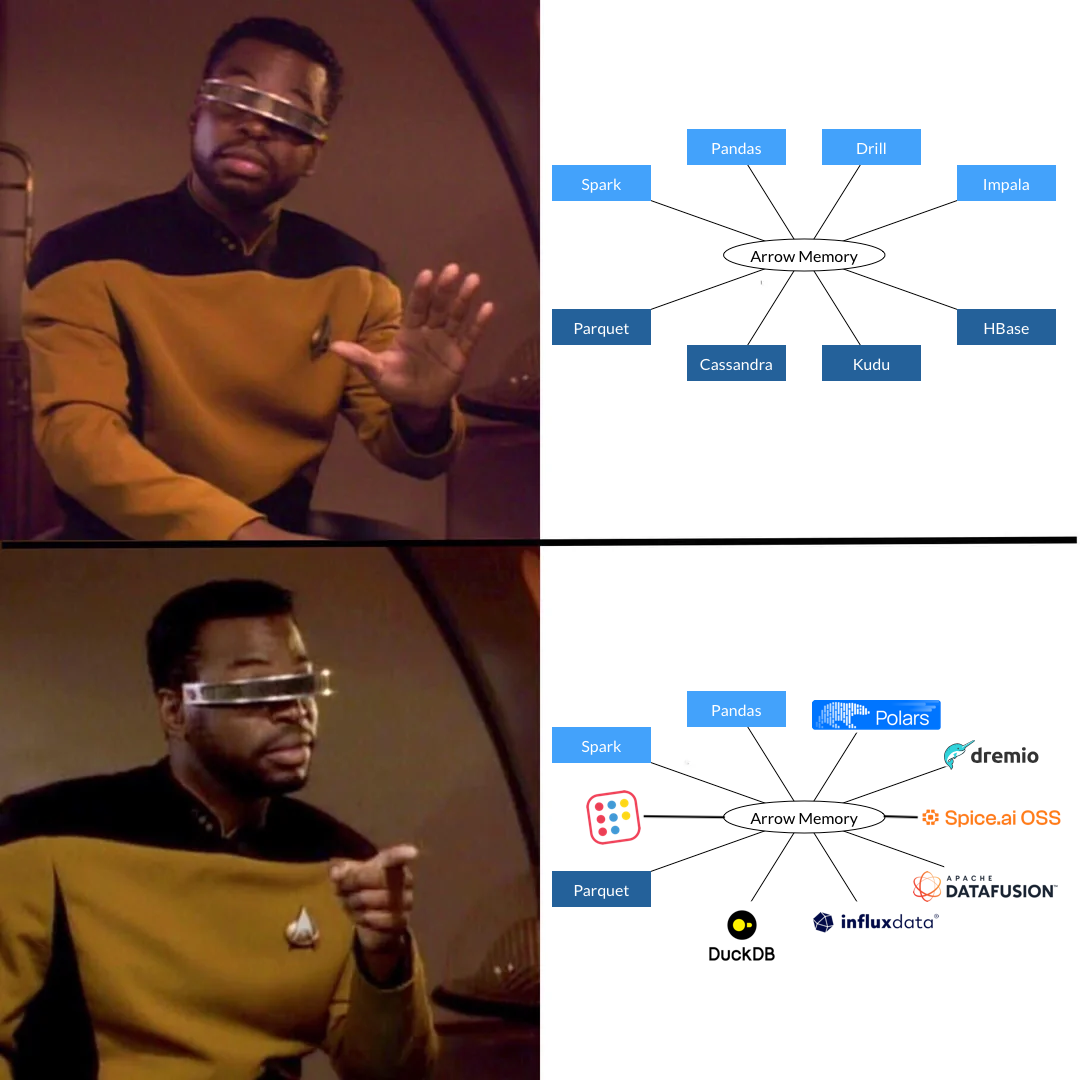

Let’s look back at the diagram on the Arrow website, which shows that if only Cassandra and HBase implement the Arrow format, they can exchange data more easily. Any guess as to how many of those projects there actually support Arrow today?

Most did not! We showed the value of reading Parquet files into Pandas using Arrow, and of going back and forth to Spark, but the others did not implement Arrow. But those projects are the previous generation: instead, Arrow built credibility over time, and the next generation chose to build on Arrow from the beginning.

So the reality is more like this:

What about the next next generation?

Now we’re here, ten years in, and Arrow is everywhere. It’s taken for granted that if you’re building a data system, you’re using Arrow. But what about what comes next? How do we make sure that Arrow continues to be the foundation for the next next generation of data systems? There will always be innovation in data systems, query engines, hardware, programming languages, and so on. And there will always be incentives to try to make something just work for your product, to re-bundle what is being deconstructed now. How do we make sure that the developers of those systems choose to build on Arrow, rather than going their own way?

In other words: when someone prepares the “Arrow Turns 20” talk, what will they say?

Our culture will make the difference

This is where I believe the culture of the community really matters. If we remain open to new ideas and new people, and if we actively welcome them and support them in becoming repeat contributors, then we will be well-positioned to continue to grow and evolve the Arrow ecosystem. This culture is essential to the long-term sustainability of the project.

The challenges we will face will be very technical, of course! Finding the best technical solutions to navigate these tradeoffs will be essential. But our openness and inclusivity will be our superpower—that’s what will make sure that the best technical minds keep coming to work with Arrow and engaging with the community.

So, to conclude, I feel like there’s some cliche I should land on. Perhaps: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” Or, calling back to my initial self-reflection, “It takes a village to raise a child.” Or maybe just “Choose kindness.”

There are lots of ways to run an open source project, or really to exist in the world. Maybe it’s possible to brute-force your way to ubiquity with just technical merits, by aggressively pushing your technical superiority and proving you’re right. But ultimately, I skeptical that that’s sustainable. And it’s not something I would want to be a part of anyway.

A healthy culture is important for our sustainability. I believe we have a solid cultural foundation now. And in many ways, culture is self-reinforcing: it attracts people who share those values. Moreover, I don’t see anything that makes me concerned that we’re losing this welcoming culture.

But I wanted to take some time to highlight the importance of this culture, and to encourage all of us to continue to nurture it, because sometimes we don’t appreciate the importance of values and norms until they are gone. Not to drag my country’s current political situation into this, but it is a good object lesson in how the same formal institutions can lead to wildly different outcomes when there is a shift in norms around what is acceptable.

I want to end on a note of gratitude. If you’re already an Arrow contributor or maintainer, thank you for your contributions and dedication to this radical social project. The community and values I described here, to say nothing of the technical achievements, would not be possible without you. It’s been such a privilege to get to work alongside many of you over these years, through some ups and downs, and to get to learn so much from you.

If you haven’t gotten involved with the Arrow community before, welcome! We’re glad you’re here today, and I hope you’ll stop by the project on GitHub, join the mailing lists if you like, and please don’t hesitate to share any feedback or ideas for how we can improve things. Of course, as I mentioned, you may get invited to submit a pull request to address something you reported, and who knows where that might take you.

And finally, thank you again for coming today and listening (er, reading).